There’s a long-held fable within investing circles that surging M&A activity can (at times) signal a market top. So, how does that come about?

Just like regular investors, major corporate executives suffer from the same psychological condition known as FOMO.

The ‘fear of missing out’ is a timeless human condition repeated for eons and ingrained in human DNA. Yet, it seems to hold a special place in the mining industry.

A psychological condition that extends from the small-scale investor to the top dog at a major mining firm.

That’s why M&A activity can offer a useful barometer for gauging positions in a broad commodity-wide cycle. It’s the scale judging overall market hubris or lack thereof.

But the first, perhaps most important point: a single large deal, such as BHP’s (NYSE: BHP; LSE: BHP; ASX: BHP) now-cancelled recent bid for Anglo American (LSE: AAL) shouldn’t cause concern.

In other words, the formation of a major top.

Almost 20 years ago, BHP was in pursuit of another major mining corporation.

Like Anglo, BHP was after an established, multi-commodity producer with a deep history of mining. The company in the majors’ crosshairs was WMC, formally known as Western Mining Corporation.

Founded in 1933, WMC built a legacy of finding world-class deposits and bringing them into production.

This was one of the country’s most iconic companies, pivotal in making Australia’s mining industry world famous.

It discovered one of Australia’s largest mines, the giant copper-gold Olympic Dam deposit in South Australia. Since its discovery in 1976, this project has continued to deliver rich rewards to its owners.

But in 2005, BHP paid a lofty AUD$9.5 billion (US$6.3 billion) for WMC and its basket of assets. That’s equivalent to around AUD$15.4 billion in today’s money.

Far from the top

As the WMC acquisition showed, 2005 was far from a market peak. In fact, commodities continued to rally for another six years into 2011.

Like today, 2005 was the beginning of something much larger.

Yet, the sheer number of M&A deals taking place can measure the market’s boiling point. That occurred on two occasions over the last commodity cycle:

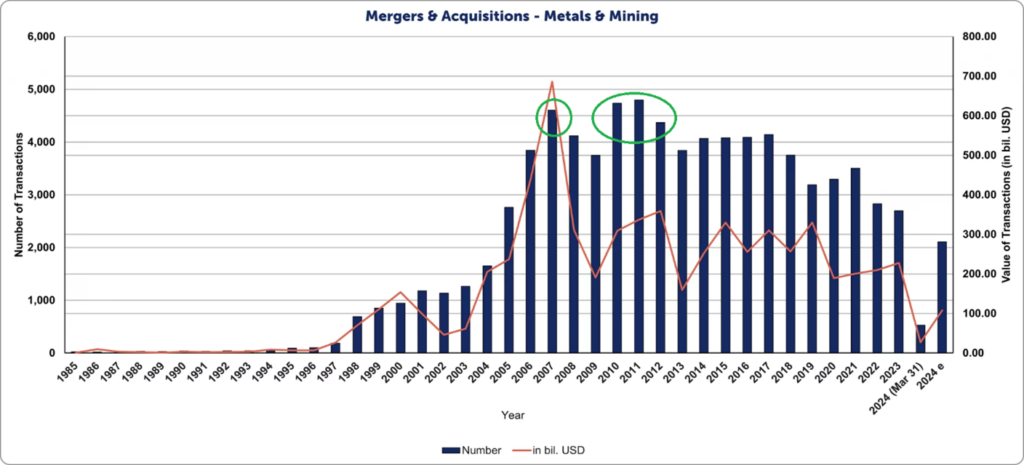

Source: Institute for Mergers, Acquisitions & Alliances

Here, blue bars represent the number of deals; the brown line measures their overall value. I’ve The M&A peaks are shown as green circles.

The year 2007 was a lofty one for acquisitions.

That successfully pinpointed a top in commodity markets before the 2008 subprime crisis took hold. Commodity prices fell sharply and M&A activity cooled.

That was only temporary. A second green circle shows the next peak in M&A activity over 2010-12.

This was a truly spectacular time for commodity markets.

M&A on steroids

The 2010 to 2012 period would mark the finale of one of history’s most euphoric commodity booms.

As a geologist working in Zambia for Equinox Minerals at the time, I had a unique on-the-ground perspective.

In early 2011, Equinox was under a takeover bid offer from the Chinese-owned mining conglomerate MMG. A few weeks later, Barrick Gold (TSX: ABX; NYSE: GOLD) trumped MMG with a US$7.3 billion takeover offer.

That was enough for Barrick to grab hold of Equinox’s copper assets.

Symbolically, the deal took place just a few weeks after copper reached what was at the time its all-time high of around US$4.48 per lb. in February 2011. Barrick had captured its prize, but the excitement was short-lived.

As the above graph showed, M&A activity was feverish alongside historically high commodity prices.

But as some may remember, the rush to acquire projects and outbid competitors came at a great cost.

Just two years later, Barrick, the world’s largest gold miner at the time, suffered a humiliating US$4.2 billion write-down on the Equinox deal.

Barrick’s CEO admitted in shareholder communications that the mining giant grossly overpaid in its race to grab this Zambian copper asset.

A few months later, the company’s CEO was given the boot.

Clearly, mining executives are just as prone to overpaying as the everyday investor.

And Barrick was far from alone in this race to the bottom.

In 2013, the CEO of mining giant Rio Tinto (NYSE; RIO; LSE: RIO; ASX: RIO), Tom Albanese, was fired after the company wrote off more than $14 billion following a series of poorly timed acquisitions.

BHP, Rio Tinto, Barrick, Glencore (LSE: GLEN) and many others participated in the M&A folly that took place at the peak of the last mining boom.

Undoubtedly, the next generation of mining executives is destined to repeat the same mistakes, as are the legions of investors.

But what does BHP’s latest move on Anglo signal? Is it a measured takeover attempt akin to BHPs 2005 acquisition of WMC?

Or does it represent a market full of hubris, counterbids and excessive premiums?

Clearly, it’s the former. We’re still far from a 2011-style top.

Despite elevated commodity prices, junior mining stocks continue to trade around multi-year lows.

This is a key reason investors should be looking at this sector from a value perspective.

— James Cooper runs the commodities investment service Diggers and Drillers. You can also follow him on X (Twitter) @JCooperGeo

Be the first to comment on "M&A activity shows we’re far from a market top in commodities"