In a short essay titled Making sense of the gold price, Paul van Eeden of Rick Rule’s San Diego-based Global Resource Investments makes a compelling case for buying gold to protect against a weakening U.S. dollar.

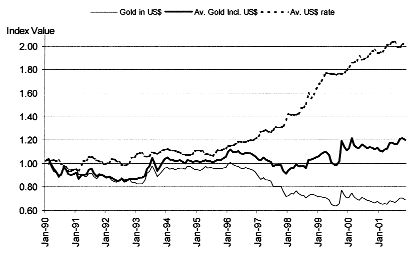

Van Eeden provides a highly revealing 12-year graph of the gold price relative to both the U.S. dollar and to a basket of 51 major currencies weighted according to gross domestic product.

The graph shows that even though the gold price in U.S. dollars has declined by over 30% since January 1990, the average gold price in the world has increased by more than 20% during the same period and by 30% in just the past four years. This, he says, is a “strong indication that gold is still a safe haven for capital.”

The decline in the U.S.-dollar gold price, van Eeden explains, is due to the strength in the U.S. dollar, so that “when we talk about the gold price in U.S. dollars, we are by definition also talking about the U.S.-dollar exchange rate.”

He then runs through a series of examples, from the past 10 years, that illustrate how gold has acted as a safe haven for capital during times of financial turmoil:

– In 1992, the Brazilian real crisis began and the U.S. dollar strengthened 15% by January 1994 as capital left Brazil. The average gold price responded by rising 24% while the U.S.-dollar gold price rose only 13% — the lag being due to the strength in the dollar.

– From November 1994 to February 1996 the U.S. dollar rose another 5% as the Mexican peso fell. The average gold price rose by 10% while the U.S.-dollar gold price rose only 6%, again owing to the dollar’s strength. Gold in Mexican pesos shot up 107% in less than three months.

– By July 1997, with the onset of the Asian crisis, the dollar had already gained another 10%. The average gold price declined by 10%, but those holding gold assets in the affected countries saw strong gains: Indonesian investors saw gold prices rise by 375% in seven months; gold in South Korean won increased by 100% in five months; gold in Malaysian ringgit rose by 80% in six months; and gold in Philippine pesos increased by 67% during the same six months.

– From July 1997 to July 1998, the U.S. dollar gained 15% as the world continued to reel from the Asian crisis. The average gold price remained essentially flat while the U.S.-dollar gold price lost 10%.

– In August 1998, Russia defaulted on its debt and devalued the ruble so that by December of that year, the U.S. dollar had gained yet another 10%, as did the average gold price. Thus, even as the dollar-gold price remained unchanged, Russian investors saw the price of gold rise by 307% in eight months, and it has continued to increase ever since.

– in South Africa, investors have seen the price of gold steadily rise 180% over the past nine years.

Van Eeden notes that in each case, the average gold price responded to the crisis even though the U.S.-dollar gold price did not necessarily do so.

“But the world has become fixated on the dollar-gold price,” writes van Eeden, “and it has become generally accepted that gold has lost its value as a store of wealth. From the above examples, however, it should be clear that nothing is further from the truth.”

Fall in the euro

The same pattern can be seen as well in the short life of the euro: In January 1999, the euro was launched at 1.17 to the dollar, after which it promptly fell 25% against the dollar; during the period, the average gold price increased 13% while the U.S.-dollar gold price remained essentially unchanged.

Overall, the U.S. dollar increased 105% from January 1990 to the present, the average gold price increased by 20%, and the U.S.-dollar gold price decreased by 30%.

Furthermore, van Eeden calculates that, were it not for the increase in the dollar-exchange rate, the U.S.-dollar gold price would today be above US$500 an oz., and were it not for the 20% increase in the average gold price, the U.S-dollar gold price would now be under US$200 per oz.

As for the decline in the average gold price from February 1996 to August 1998, van Eeden says it was caused by the vast amount of gold that was mobilized in the gold-carry trade, whereby central banks would lend out their gold to bullion banks that, in turn, would make gold loans to mining companies and hedge funds.

When Russia defaulted on its debts in 1998, central banks re-evaluated their counter-party risk, resulting in a 25% drop in gold-lease rates to an uninspiring 1.5% per year.

Investors in the U.S. have not yet experienced an increase in the gold price, owing to the country’s robust economy and extremely strong stock market of late.

“However,” van Eeden asks his readers, “now that the ‘New Era’ has been discredited, the economy is stalling, corporate earnings are falling, bankruptcies are at record levels and the stock market is shaky, shouldn’t you be thinking about some financial insurance and a safe place to put some of your capital?”

Bretton Woods

To provide a better understanding of the U.S. currency today, van Eeden takes a look back to the 1960s, when the U.S. dollar was the de facto reserve currency of the world and it remained directly convertible into gold at a fixed price of US$35 per oz. under the Bretton Woods agreement.

But the Bretton Woods system of fixed major currencies started to become unworkable in 1965, when the U.S. began a strong expansion and moderate inflation of the dollar in order to finance the Vietnam War and President Lyndon Johnson’s “Great Society.”

A resurgent West Germany and Japan urged the U.S. to curb money supply, tighten credit and cut government spending, but instead, the U.S. continued its expansion so that West Germany and Japan were forced to dive into the currency markets in order to maintain their respective currencies’ exchange rates.

By 1971, Bretton Woods currencies were allowed to float freely against the dollar, and President Richard Nixon halted gold convertibility in response to a massive flight out of the dollar.

“Recall that in 1946, the U.S. owned about 80% of all the gold in the world,” writes van Eeden. “By 1963, the U.S. gold reserve barely covered liabilities to foreign central banks, and by 1970, the gold coverage had fallen to 55%. By 1971, it was a measly 22%.”

Inflation was thus unleashed in the U.S. and it ran rampant during the rest of the 1970s. The gold price rose from US$35 per oz. to more than US$700 per oz. before settling into a trading range of around US$400 per oz., where it remained until February 1996.

“The current powers that be, although they are intimately familiar with the events of the seventies, would very much like to experience the thrill of defeat for themselves,” writes van Eeden. “Portfolio adjustments among central banks continue to replace gold with dollars, but this time the inflation of the dollar, which should lead to a new round of devaluations, is much more severe than it was in the seventies. The U.S. dollar has never been as prevalent in the world as it is today. The stage is set.”

During the past seven years, van Eeden argues, the U.S. dollar has been artificially strong as a result of the foreign-currency crises (outlined above) and in spite of the facts that the U.S. has embarked on a policy of domestic monetary expansion and the U.S.-trade deficit has increased the foreign supply of dollars at an unprecedented pace and to historical levels.

“In spite of similar economic growth leading up to 1971, higher interest rates and less debt [than in the U.S. today], the bottom fell out of the dollar during the following ten years,” writes van Eeden. “Could a similar surprise be in store for us?”

He concedes that faith in the U.S. dollar today is based on faith in the U.S. economy, unlike the time prior to 1971, when there was a forced dollar-exchange rate.

On the other hand, he sees a host of troubling economic data coming out of the U.S. — a rapid growth in money supply; the longest string of industrial-production declines since the Great Depression; shrinking corporate revenues and profits, which are resulting in spending cutbacks and layoffs; an un

precedented series of interest-rate cuts by the Federal Reserve; heavy debt loads carried by companies, individuals and governments; and a decline in consumers’ savings rates to virtually zero.

Van Eeden writes that a combination of reduced corporate spending on capital goods and falling consumer spending is likely to devastate the U.S. economy: “We probably have about US$8 trillion that has to be wiped out of stock portfolios before we should start looking for the bottom of this bear market. I cannot imagine any amount of government stimulation that can prevent this from happening.”

He believes that further contraction in the U.S. economy could cause foreigners to rethink the US$400 billion they invest annually in the U.S. From there, any decline in demand for the dollar to buy U.S. assets should lead to a drop in the dollar-exchange rate.

“The most likely outcome . . . is that we are going to have a declining stock market, a short period of deflation followed by a nasty bout of inflation in conjunction with a stagnant, or declining economy and, on top of it all, a declining dollar,” writes van Eeden.

“Since the gold price is inversely related to the U.S.-dollar exchange rate, the gold price should rise if the dollar declines. Gold appears to be the single best investment for anyone interested in capital preservation today.”

A copy of van Eeden’s report and additional gold-related commentary are available at his web site, www.pve.net

Be the first to comment on "What’s in store for the US dollar and gold?"