MAYO, YUKON — To prospectors, Yukon and gold are almost synonymous, an equivalence the territory earned by churning out 20 million oz. placer gold. It is odd to think, then, that Yukon has never been home to a significant hard-rock gold mine.

Victoria Gold (TSXV: VIT; US-OTC: VITFF) is trying to change that. The company has economically sound, fully engineered, permitted plans to turn its Eagle gold deposit, part of the Dublin Gulch property in central Yukon, into an open-pit, heap-leach mine producing 192,000 oz. gold annually for nine years — longer if other gold targets on the property pan out.

The problem is money. Capital costs are pegged at $383 million. Add $17 million for pre-strip work and another chunk of working capital, and Victoria Gold figures it needs $430 million to get Eagle into production.

The company started the search for those funds in 2012. In the interim it has secured permits to build the mine and signed a co-operation and benefits agreement with the Nacho Nyak Dun First Nation, on whose land the project lies.

Eagle is ready to be built. Unfortunately, today’s markets mean the money is not readily available.

So gold-famous Yukon continues to await its first major gold mine.

Dublin Gulch is a large land package, 550 sq. km in total, located 80 km northeast of the town of Mayo in central Yukon. It is road accessible and grid power reaches within 45 km of site.

The ground is part of the Tintina mineral belt, a tectonically thickened, gold-rich rock package north of the Tintina fault that cuts east–west across Yukon. At Dublin Gulch a granodiorite pluton intruded the Hyland Group metasedimentary rocks. The event left both the granodiorite and the sediments fractured and quartz veins emplaced, along with gold.

Victoria acquired the project in 2009 when it took over StrataGold. At the time, the project offered 2.7 million indicated oz. gold. By early 2011 Victoria’s drilling, metallurgical testing, and expanded pit design boosted that count by more than 50%, to 4.8 million indicated oz. contained in 222 million tonnes grading 0.68 gram gold per tonne. A higher gold price and a lower cut-off grade also helped.

Victoria fed its enlarged resource into a feasibility study that wrapped up in early 2012. It outlined an open-pit mine that, over nine years of operation, would take out the top and side of the hill that houses the Eagle deposit.

That advantageous topography means the strip ratio at Eagle is favourable, averaging 1.4 tonnes of waste for each tonne of ore over the mine’s lifespan. McConnell says the strip ratio has improved since the study because infill drilling upgraded some inferred resources to indicated status, enabling their inclusion as reserves.

The mine would move 29,500 tonnes of ore daily, crushing the rock and placing it on a valley-fill, heap-leach pad. A 150-day leach cycle should recover 72.6% of the contained gold. An on-site adsorption-desorption gold recovery plant would take the gold from the pregnant leach solution and turn it into doré bars.

John McConnell, Victoria’s president and CEO, is often asked whether a heap leach will really work at Eagle, where temperatures through the winter months range from -18°C to -31°C. In response he simply points north, to Kinross Gold’s (TSX: K; NYSE: KGC) Fort Knox heap-leach mine.

“The independent engineers from the banking syndicate — we took them up to site and they were all skeptical,” he says. “Then we chartered them over to Fort Knox and the guys there toured them around and all their apprehension about working in the north disappeared. It was really an eye-opener. Lots of people have that concern until you take them over to Fort Knox.”

Fort Knox is near Fairbanks, Alaska, where winters are even colder than at Eagle. Yet the heap leach at Fort Knox reliably recovers 65% of the ore’s contained gold, and the operation has produced better-than-expected recoveries. Kinross is commissioning a second leach pad that is identical to the first.

Eagle’s resources slim down to 91.6 million proven and probable tonnes of reserve, with a grade of 0.78 gram gold. The deposit’s highest gold grades are near surface: in the first three years of operation the operation would churn through 21.6 million tonnes of ore grading 0.94 gram gold.

Elevated initial gold grades plus better recoveries from oxidized, near-surface ore mean Eagle could produce 211,000 oz. gold annually in its first five years. The life-of-mine output average is slightly lower, at 192,000 oz. gold annually.

The Eagle mine could produce each of those gold ounces for an all-in cost of US$959.

Using a US$1,325 per oz. gold price and a 5% discount rate, Eagle carries a $380-million pre-tax net present value and would generate a 24.1% internal rate of return. That return would allow capital payback in 3.1 years.

Finding dollars that make sense

In September the Yukon Department of Energy, Mines and Resources issued a quartz-mining licence for Eagle, which authorizes Victoria to build and operate the mine. The company is working on a few operational permits, such as the water-use licence, but the project has cleared its biggest hurdle.

Eagle’s economics and risk profile are good enough that Victoria has access to a big chunk of debt financing. It just has not accepted the offer.

“In midday 2013 we engaged Rothschild as an advisor on financing and started working with a syndicate of banks,” McConnell says. “They engaged a third-party engineering company to review the feasibility, who signed off [year-end 2013]. At that point we could have signed off on a mandate letter on debt financing to the tune of $250 million.”

Rather than jumping on that opportunity, McConnell and his team stepped back and assessed the broader situation. To get Eagle into production is going to cost north of $400 million, so the debt deal would still have left a gap of $150 million or more.

“People would normally fill that with equity or selling a gold stream, or some kind of convertible debt,” he said. “We looked at a gold stream and pretty much had one lined up for $100 million, but that still left a $50-million gap. And as everyone knows, for the past six months the equity markets have essentially been closed.

“So with the gold price dropping and the markets shut down, nine months ago we told the banks we weren’t in a position to sign a debt mandate letter, because then you start incurring a bunch of fees.”

McConnell says Victoria’s management team meets with the banking syndicate regularly.

“They’re still ready to do the debt financing,” he says. “They’re not as concerned about the gold price as everybody else. They use a US$980 per oz. gold price long-term, and by their numbers, it’s still a good project — at US$980 per oz. it pays back the debt. But we have to wait for the equity markets to open up.”

Equity is not the only option. McConnell says Victoria is also talking to potential joint-venture partners.

“Maybe the best way to finance Eagle is to sell 50% of it,” he says. “We’re looking at those options too.”

Victoria already built a 100-person camp at Eagle, ready to accommodate construction workers. At full operation the mine will employ 350 to 400 people, but today the camp is mostly empty. When The Nort

hern Miner visited in August there were just a few Victoria employees on site, to keep the place ready for visitors.

The company’s office has a similar feel. To conserve cash Victoria laid off 65% of its staff in mid-2013, including two board members. The company also gave up more than half of its office space and curtailed the remaining detailed engineering work.

“It was a tough decision. You’ve got the team, the people, the project — you want to be: ‘Rah-rah, let’s get it done!’” McConnell said. “And then instead you’re laying people off. But in hindsight it was the right decision.”

Victoria is using the downtime to optimize the project. For example, McConnell says his team is assessing whether it makes sense to incorporate a small liquefied natural gas power generator on-site, to supplement the grid power.

Proving up more reserves is also back on the company’s to-do list. Victoria had stepped away from exploration in recent years, as the focus was on engineering and permitting the Eagle operation. With those tasks essentially complete, McConnell says they are ready to return to some of Dublin Gulch’s satellite zones.

“In our January board meeting we did approve an exploration budget for this year of $2 million,” he said in a March phone interview. And Victoria knows exactly where and how it will spend those dollars.

“These tough times have freed up some good people, so last year we hired an exploration geologist with a lot of experience and had him look at the satellite zones,” McConnell said. “These targets had been looked at on and off over the last 20 years, so he pulled all the data together and said, ‘The best prospect you have is Olive, and I think there’s potential there for 25 million tonnes at 1.5 grams gold.’ That’s almost double the grade of Eagle, so that is going to be our focus.”

Olive sits 2 km from the Eagle mill site and has seen 35 drill holes and several rounds of trenching. The zone has offered high gold grades, including a grab sample that carried 189 grams gold. Geologically the zone hosts thick, discrete high-grade veins and more widespread, low-grade veining. Eagle, by contrast, only offers the latter.

Work to date has outlined a zone striking 820 metres north–south, stretching across 150 metres wide, and extending to 250 metres deep. It remains open in several directions, and mineralization starts right at surface.

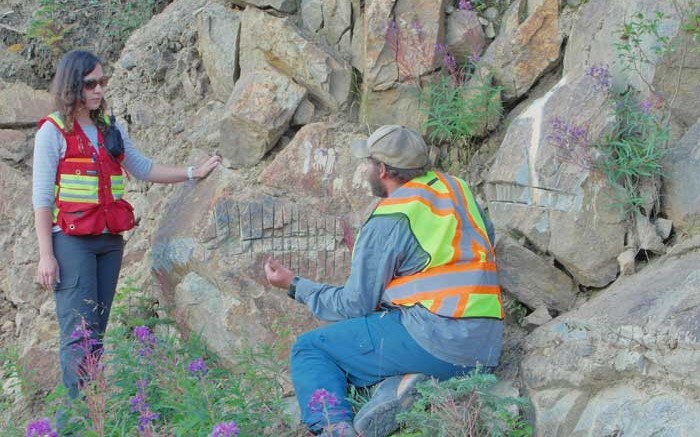

“Anywhere else in the Yukon this is a project-making deposit right here,” said Patrick Sack, an economic geologist with the Yukon Geological Survey, standing in the Olive zone. “Here it is just second fiddle.”

“We’ve budgeted $2 million, and if we’re successful, we’ll probably spend another $2 million to take it from a resource to a reserve, so we can include it in an updated feasibility study,” McConnell said. “It’s a good time to do that now. You don’t want to be changing the project scope halfway through permitting. But now that we’re permitted, if Olive does look good, we could apply for a licence amendment to start mining there.”

When mining starts, though, is anyone’s guess. As of the end of November, Victoria had $27 million in cash and equivalents — enough to keep the company afloat for several years while it searches for capital. In the meantime, Yukon remains a placer-gold legend bereft of a major gold mine.

“We’ve produced 20 million oz. placer gold in the Yukon, but I don’t think we’re mined half a million ounces of gold from hard-rock mines,” Sack said. “If Victoria builds this mine, in three years it will produce more gold than has been produced from all the hard rock mines in the history of the Yukon. And that would be pretty great.”

Be the first to comment on "Victoria Gold’s mission: Build Yukon’s first major gold mine"