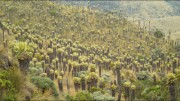

There is a whole lot of verdete slate at Verde Potash‘s (NPK-V) unconventional potash play in Brazil. Standing atop a hill of the chalky green rocks, you can see the same rocks poking conspicuously from the many grass-covered hillsides in the distance. The rocks are so plentiful they are used as aggregate on roads, and so near-surface that termites have gone and made homes out of the stuff.

The numbers being thrown about only reinforce the size of the company’s Cerrado Verde project. An initial resource covering a small section of the 120-km-long trend came in at 160 million inferred tonnes, with the overall potential noted in the billions of tonnes. A preliminary economic assessment, based on a higher cut-off inferred resource of 105.1 million inferred tonnes grading 10.3% potassium chloride, outlined a potential 137-year mine life.

Such plenitude helped draw Verde to the project in 2008, president and CEO, Cristiano Veloso, explains during a visit to the project.

“It was a property where there was no real exploration risk,” Veloso said. “You could see it had lots of potash. So we wouldn’t be getting into a scenario of crisis where we would need to invest money on exploration with a high risk, it was more market development.”

The company needed to develop a market because, while this plentiful resource has been known since the 1960s, no one has actually managed to sell any of it.

But Verde hopes to change that by transforming the otherwise useless glauconite-based rocks into potentially valuable “Thermopotash.” Decades ago, Vale (VALE-N) looked into the potassium-rich rocks at Cerrado Verde as a potential source of fertilizer, and found it could create a potash alternative by cooking the rocks at high temperatures, and adding limestone. In this way, Thermopotash was born.

The product has a lower potassium oxide grade than more conventional potash, but it is also low-chlorine, requires farmers use less limestone on their fields, and its low solubility means the nutrients are released slowly and not washed away by Brazil’s heavy rains.

But the cost of roasting the verdete over 1,000°C was high, and local demand was relatively low, so Vale abandoned the project and let the claims lapse.

The situations in Brazil and the potash market have since changed dramatically. The agricultural sector has exploded, and fertilizer prices have followed suit. And there, in the middle of this boom, sits Verde Potash and its sizable resource, waiting to reap the benefits of a well-timed land play.

A PEA and market studies confirm that Verde could make a respectable profit from Thermopotash. A second technological breakthrough – currently in the works, and patent-pending – could radically change the company’s fortunes.

Humble beginnings

Verde Potash, which recently changed its name from Amazon Mining, did not begin as a potash company.

When Veloso started the company in 2005, he was intent on finding far more alluring gold. A native of Brazil’s mining capital Belo Horizonte, he was familiar with the country’s one-time status as the world’s largest exporter of gold (albeit in the 18th century), and wanted to make the most of his local experience to advance projects.

His experiences as a 24-year-old, however, were somewhat limited. But fresh from completing an advanced degree in international business law, following two earlier degrees, Veloso gathered seed capital for the private venture, and was ready to spread his entrepreneurial roots.

“I’ve always been a bit of an entrepreneur,” Veloso says, recounting how he ended up running a mining company at an age when most are trying to get hired by one. “Mining was a part of my life growing up, and it just came as natural when I started.”

The company found limited success with early properties, but debuted on the TSX Venture Exchange with a $16-million initial public offering at $1.20 in late 2007. A year later, the company traded at barely 20¢, and change was afoot.

Lured by a steep increase in potash prices, which in Brazil peaked at around US$1,000 a tonne in 2008, Veloso led the company out of gold and into potash. He encountered strong resistance, but with the company having already abandoned three gold projects in 2008, Veloso fought for the change in direction, and won. So the team got to work.

“When potash prices started going up,” Veloso says, “we sat down with our exploration team, and we carefully looked at every single opportunity on potash in Brazil.”

Veloso said the team found environmental and social problems with the obvious potash prospects in the Amazon Basin, and obstacles for properties surrounding Vale’s Taquari-Vassouras mine in Sergipe state, the only active potassium mine in Brazil.

The most interesting project turned out to be a potassium silicate property that Ysao Munemassa, Verde’s current exploration manager, had worked on with Vale long ago. Munemassa pointed Verde to the property’s still unrealized potential, and helped identify the best ground. In return, he got a 3% royalty on the property, which Verde can buy for $3 million at any time.

Verde went on a staking rush to secure as much choice land as possible, even claiming some areas as diamond and phosphate licenses to avoid suspicion. The efforts proved wise. Vale swooped in shortly after, and staked a large land package adjacent to Verde.

On Nov. 24, 2008, Verde announced it had amassed a 1,650-sq.-km land package that represented a “major Brazilian potash opportunity,” and a new direction for the company. Shortly after, the company’s share price hit an all-time low of 7¢.

Out of Necessity

The next year was one of patience. Verde worked to prove up a resource, and prove to investors that verdete slate – and the Thermopotash made from it – were indeed worthwhile commodities.

The company amassed a who’s who of research and development partners. The Brazilian government-sponsored Centre for Mineral Technology signed on, as did the research program Agrominerais. Embrapa, Brazil’s main agricultural research corporation, the University of Uberlandia, and the University of Lavras would also all eventually research the practicability of Thermopotash.

The government of Minas Gerais, meanwhile, fully endorsed the idea, and promised preferential tax treatment, support in financing the project and help with the approval process.

Later in 2009, ArcelorMittal (MT-N) signed up to test Thermopotash, as would Agrifirma Brazil, a UK-based agriculture firm, while Sekita Agronegocios, a leading Brazilian agribusiness, signed on in early 2010. Sekita, a major vegetable-grower in the country, planned to test the product in “real world conditions,” which led to rather unwelcome results.

The pedigree of parties interested in Verde’s science project was a testament to their curiosity in the product and, in a way, their desperation. Brazil has quickly become one of the world’s leading consumers of fertilizers, importing over 90% of its potash. The country is expected to be the world’s largest potash importer by 2020.

The demand has been sparked by the agricultural revolution of the Cerrado. Thanks to early research by Embrapa, and a healthy dose of limestone and fertilizer, the once-barren expanse has been transformed into one of the world’s great agricultural regions.

The country is now the world’s largest exporter of coffee, sugar cane and ethanol, to name a few, which comes as no surprise after seeing endless lush green fields filled with cash crops on a drive across Minas Gerais. Veloso has witnessed the transition first-hand.

“Back in the seventies and eighties . . . there was nothing, they couldn’t grow anything in the Cerrado region of Brazil. It was a very different scenario to what it is today,” Veloso says.

Brazil’s agricultural industry has littl

e stopping it from growing much bigger. The country has the world’s largest stores of renewable fresh water, a dynamic and educated workforce, a climate that allows up to three growing cycles a year and, thanks to the Cerrado, by far the most potential new arable land in the world.

All Brazil lacks is fertilizer.

Milestones

Verde is proposing to help fill the fertilizer gap by using Thermopotash as a 15% blend in existing nitrogen-phosphorus-potassium blends, or NPK blends. Two significant studies help validate its plan.

A market study that looked at potential pricing of the Thermopotash estimated a price in Minas Gerais of US$182.31 per tonne, or US$160.04 delivered, while with delivery to other states, the adjusted price ranged from US$63.68 to US$130.13 per tonne. Minas Gerais had an estimated market of 896,000 tonnes, while the total market potential was 4.4 million tonnes at a weighted average price of US$112.82 delivered.

Delivery costs are high because Brazil has a serious infrastructure deficit. Most freight moves around the country by trucks, as was evident by the two-lane highways clogged with the slow-moving machines.

Transportation is also a key part of Verde’s competitive edge compared with imports. Veloso explains that, when local blenders order potash from Saskatchewan, they must wait three months for the ship to arrive, up to a month more to unload the cargo in Brazil’s severely congested ports, and then haul it by truck anywhere from 600 to 1,000 km inland. Total transportation costs for imports run from $150 to $200 per tonne, while Verde is looking at $20 to $70 per tonne.

“Literally being down the road from where the blenders are in Brazil, immediately down the road from the biggest blending district in Brazil, it just makes it a very simple proposition,” Veloso says.

Verde’s capital costs also set it apart from most potash projects, which often run into the billions. A PEA released last fall estimates capital costs of US$196.8 million for a 1.1-million tonne a year operation, and US$269.4 million for double the output.

For the smaller, base-case model, operating costs are estimated at US$41.80 per tonne, with a capital payback in 2.4 years. The scenario generates a net present value (NPV) of US$455.4 million at a 10% discount rate, and an after-tax internal rate of return (IRR) of 32.9%.

A doubled 2.2-million-tonne option cuts operating costs by US$5.44 per tonne, payback by half a year, and boosts the NPV to US$858.1 million, and the IRR to 40.2%.

Veloso says the PEA, along with the marketing study, have gone a long way in validating the Cerrado Verde story.

“We had big expectations that it could be a success, but those were the two independent milestones that helped confirm it,” Veloso says.

Down to the details

With the basics established, Verde is now perfecting the processing, and proving it’s possible on a large scale.

For the roasting, Verde initially conducted testing on a 100-kg-per-hour facility on the outskirts of Belo Horizonte. Now, it is moving to a 100-tonne-a-day operation a little farther out of town.

John Kaiser of Kaiser Research Online – who recommended Verde to his readers when it traded under 20¢ in 2009 – was on the same site visit, and sees the ramp-up as one of the remaining uncertainties.

“There are always risks that the process does not scale up cost effectively,” Kaiser says. “What happens to your residence times? How long do you have to keep a certain volume of material in the kiln, to get the right temperature and the right chemical reaction?”

Verde has refined the process during these trials. Pedro Ladeira, VP of engineering, has extensive experience in the cement industry, which uses a very similar process to what Verde plans. He introduced an air-mist cooling system as an alternative to water, as well as using a powder rather than pellets in the initial stages, with both potentially yielding cost savings in the upcoming prefeasibility study.

Capital costs will likely go up in the next study. Robert Winslow, an analyst at Wellington West who covers Verde, writes in a recent note that the exchange rate alone is increasing anticipated capital costs. Winslow is projecting a capital cost for the 2.2-million-tonne-per-year operation of US$318 million. He notes that Verde’s assumptions include a U.S. dollar to a Brazilian real exchange rate of 1.8, but the real has appreciated around 15% against the dollar since the PEA was released.

Winslow writes that any increased capital expenditure will likely not be offset by higher fertilizer prices, especially because Thermopotash is a new product that hasn’t received government certification. He has reduced his target share price for Verde to $10.50 from $11, but is looking at positive developments, such as an updated resource for Cerrado Verde, Thermopotash product certification and a resource for the company’s Apatita phosphate project.

Verde could also get a boost when a resource estimate comes out on its limestone project, 100 km away from its Cerrado Verde project. The company recently released drill results from the target that showed an average thickness of 36 metres grading 53% calcium oxide, and less than 2% silicon dioxide. The statistics fit perfectly with the limestone requirements for producing Thermopotash and, like the verdete, its proximity is a key benefit.

“It’s just another industrial material,” Veloso says of the limestone project. “It’s all about location.”

The new resource at Cerrado Verde will come from 26,000 metres of drilling that Verde is conducting to upgrade the resource to indicated. Early results are encouraging.

Killer carrots

With several milestones reached, Verde is convincing investors of the story’s validity. The company’s stock price climbed from 60¢ in mid-2009, to a high of $10.95 in April 2011. But the climb hasn’t been easy.

“Every time someone tries to do something that no one has done before, everyone thinks, oh, it’s not going to work,” Veloso says. “If it could work, why isn’t someone else doing it?”

Low potash prices and sated local demand are key reasons it hadn’t been done, but so was the risk of trying something new, which was seen when results from Sekita came out. Conducting “real world” tests on carrot crops, the results were inconclusive, with similar productivity and quality results using potash, Thermopotash or no fertilizer at all.

Verde slipped the information at the bottom of an April 21 release about the company’s name change, and investors were spooked, dropping the company’s share price $4.01 in two days to $6.76. Verde hastily released a second release emphasizing the uncontrolled conditions, and the likelihood of residual fertilizer in the supposed unfertilized control carrot plot.

“I think that bobbled news release that they had, that was a bit of a shock to them, about how easy it is to destroy the momentum of the story,” Kaiser says.

Verde later released results showing Thermopotash was as much as 17% more effective than potassium oxide, and more than twice as effective as the controls, but market reaction was muted. After a tough June, the company’s stock recovered somewhat, closing at $7.65 on 32.3 million shares outstanding.

With a volatile market and lessons learned, Veloso seems to have adopted a cautious approach to managing expectations. This was especially apparent when he talks about, or rather, hardly talks about, Verde’s potential blockbuster development – the Cambridge Process.

Developed by Derek Fray in conjunction with the department of materials science and metallurgy at the University of Cambridge, the process converts verdete into a conventional potash product using heat and a mixture of salts. A patent was filed in December, covering the production of muriate of potash and sulphate of potash from the verdete.

Further details of the innovation ar

e scarce, but the possibility of converting verdete into standard potash significantly increases the potential market, and could be a game-changer for the company. Kaiser also notes it could add significant value.

“The Thermopotash suggests a $10 to $15 price target eventually,” Kaiser says, “but the other stuff is the one that could take it to $50 or more.” He notes that Verde belongs in a select category of companies looking at non-traditional sources of raw materials, by “using research and development, and out-of-the-box-type thinking.”

Veloso says that if testing and development go well, there could be a scoping study out on the process by the end of the year. But the company’s near-term focus is very much on starting Thermopotash production.

“We are determined to get into production, and help Brazil address its issue with fertilizer imports,” Veloso says. He has high praise for the company’s management team and board who are working to make it happen, and expresses a deep confidence in the company’s future.

“We will certainly become one of the most successful Brazilian fertilizer companies,” he says.

Be the first to comment on "Verde Potash heats up on Brazilian Thermopotash"