SITE VISIT

Yusufeli, Turkey — Have you ever wondered what happened to Vancouver’s Manhattan Minerals after its high-profile implosion in early 2004 at the Tambo Grande project in Peru, where great geology proved to be no match for fierce local opposition to mining?

Well, it was tough slogging for a while, but the company has renamed itself Mediterranean Resources (MNR-T, MNRUF-O), kicked the last bit of Peruvian dust off its shoes, and now has its hands on a highly prospective epithermal gold-copper belt that it’s developing here in northeastern Turkey.

As Manhattan Minerals, the company spent $60 million developing the technically very promising Tambo Grande massive sulphide deposits in an agricultural region of northern Peru, but was stymied by the locals’ intense resistance to plans to build a large open pit and resettle the townsfolk of Tambogrande. The Peruvian government cancelled the company’s option agreement in late 2003.

In mid-2004, seasoned mining engineer Peter Guest was brought in as Manhattan’s president and CEO with a mandate to revive the project, but he says he soon realized the idea was a non-starter, and that “Manhattan was at least as wrong as the Peruvians” in the matter.

He spent the next year writing off the project, converting $2.3 million in debt held by TD Asset Management, Dundee Precious Metals (DPM-T, DPMLF-O) and others into 4.7 million shares, getting a cease-trade order lifted, and selling off all remaining Peruvian assets to Minas Buenaventura (BVN-N) for just under US$1 million.

Manhattan changed its name first to Mediterranean Minerals and then settled on Mediterranean Resources in December 2005, when it also consolidated its bomb-out shares on a 1-for-10 basis.

Mediterranean secured a key $6.6-million equity financing in February 2006, raised another $16 million in late 2006 and early 2007, and completed its long comeback in December with a return to the TSX’s main board.

The new management team is rounded out by: Winnie Wong, who serves as chief financial officer; Jag Sandhu, vice-president of corporate development; Cheryl Harpestad, corporate secretary; and directors Mark T. Brown, John A. Clarke, Bruce McKnight, Bryan Morris and George Tikkanen.

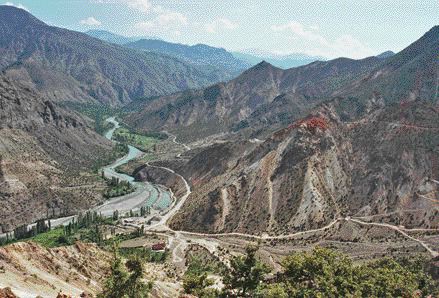

Mediterranean’s flagship Tac and Corak properties (pronounced “tash” and “chore-ack”) are situated in the Kackar (“cash-car”) mountains in the southeastern corner of Artvin province, just a short drive south of the town of Yusufeli, within the Coruh River valley.

Former owner Cominco, now part of Teck Cominco (TCK.B-T, TCK-N), spent US$4.3 million exploring for gold and base metals on Tac and Corak between 1988 and 1992, with money split equally between the two. The company then sat on the project for a dozen years.

Mediterranean optioned Tac and Corak from Teck Cominco in September 2004, and earned a 100% interest last year by issuing 2.8 million shares (a 9% stake), spending $2 million on exploration, paying another $450,000 in shares, and agreeing to pay $2 million soon after commercial production is reached.

Uncharacteristically for Teck Cominco, the major neglected to negotiate a back-in right, but it does retain a 1.75-2% net smelter return (NSR) royalty on both properties, which are also subject to small NSRs payable to the state and the original Turkish property owner.

The Kackar Mountains are widely known by hiking and whitewater enthusiasts for their rugged, sparsely vegetated peaks and rushing mountain streams.

Elevations around Tac and Corak range from 800 to 2,000 metres above sea level, and the climate is dry, with scorching summers and slightly snowy winters. Mineral exploration can be carried out year-round, except at the highest elevations, where snow accumulates during the winter.

The infrastructure is very good, with well-maintained, mostly paved roads that wind along river-valley floors to service local towns and a substantial state-owned hydroelectric power system. By road from Yusufeli (population 6,400), the Black Sea and the Georgian border are 60-80 km north, the Black Sea port of Trabzon is 150 km northwest, and the city of Erzurum — Turkey’s gateway to the East — is 100 km south.

Through a Turkish contractor, Mediterranean is carrying out its own extensive and rapid road building up steep mountainsides at both properties in order to get its drills to the right spots.

The 15-sq.-km Tac property is 8 km southwest of Yusufeli, and the 8-sq.-km Corak property is another 10 km beyond that. While Corak looks for the moment to be the more prospective of the two, Tac was advanced a little more by Cominco because it was closer to town.

Geologically, the properties lie within the Pontide belt that extends several hundred kilometres from the Black Sea and structurally overlies the Tauride belt to the south. The Pontide is dominated by island-arc volcanic and sedimentary rocks that were deposited on a Paleozoic basement of granites and schists.

South-directed compression has deformed the belt into alternating east-trending zones of compression and extension, with Tac and Corak nestled in extensional zones.

There are plenty of thrust faults on the properties, marked at surface by extensive, though shallow, coincident zones of argillic and hematitic alteration.

The key understanding is that the region’s gold and base metals mineralization tends to be controlled by structures rather than lithology.

Tac property

The Tac property is almost entirely underlain by southeast-dipping, Upper Cretaceous to Eocene-age andesitic volcaniclastics and flows, with some overlying turbidite sedimentary rocks to the southeast. Many of the highest peaks on the property (called “Tepes”) are in fact silica caps.

Following up on a bit of regional geochemical work by United Nations personnel in 1972, Cominco’s exploration team carried out surface rock and soil sampling, and drilled 34 shallow reverse-circulation (RC) holes (totalling 1,900 metres) and 10 diamond-drill holes (1,700 metres).

Because of the forbidding terrain and limited road-building budget, Cominco’s holes at both properties were mostly drilled at low elevations near the valley floors, and thus only gave a hint at Tac and Corak’s true potential.

Still, Cominco found significant gold and copper mineralization at Tac plus minor silver, zinc and lead, all within a classic high-sulphidation epithermal gold-base metal environment.

The mineralization occurs in quartz veins that are usually a few centimetres thick and sometimes crosscut to form wider vein networks. Gold is found in both high-grade narrow veins and broad zones of low-grade material.

Overall, the gold-mineralized trend at Tac — dubbed the “gold corridor” — extends at least 2-3 km in length and has a width averaging 300 metres.

It’s still not clear whether the corridor would best be exploited as a bulk, low-grade open-pit operation or as a higher-grade, low-tonnage resource with veins selectively mined from underground. Either way, acid drainage would be a concern with the ore’s high sulphur content and the Coruh River being so close to operations.

In 1992, Cominco tallied a rough resource of 5 million tonnes grading 2 grams gold per tonne, but this is not compliant with National Instrument (NI) 43-101.

In 2006, Mediterranean spent $3.1 million at Tac to complete a 15,000-metre, 63-hole infill drilling campaign plus a 13-line-km induced-polarization survey and some mag work — all of which was managed by Teck Cominco under a service contract that ended in March 2007.

The drilling was subcontracted to Ankara-based Spektra Drilling, which continues to be the project’s drilling contractor. Rock samples are sent to ALS Chemex in Izmir in western Turkey for preparation and then shipped to ALS in Vancouver for final assaying.

Wardrop’s Vancouver office calculated a NI 43-101-compliant resource at Tac in February 2007, incorporating results from the 2006 drilling.

Within Tac’s two most-explored min

eralized zones — named Copper Creek-Ugur Thrust (CCUT) and Karsibayir — Wardrop tallied 11.8 million indicated tonnes grading 1.8 grams gold per tonne and 0.13% copper (or 638,000 contained ounces gold and 34.2 million contained pounds copper), plus another 390,000 tonnes of inferred material at slightly higher grades.

Last spring at Tac, Mediterranean took over as project operator, and the emphasis changed to expanding the CCUT zone to the northeast and downdip. Mediterranean completed another 7,500 metres of drilling by the end of 2007, spending a combined $5 million exploring Tac and Cornak.

Drilling highlights at Tac include: a shallow 56 metres of 4.18 grams gold in hole TD-43 in the T-6 Valley zone; and 38 metres from surface grading 0.71 gram gold in hole TD-44 in the Karsibayir zone.

In May 2007, Mediterranean brought on board the 4-year-old Turkish engineering firm Dama Muhendislik to oversee project development at both Tac and Corak, including community relations.

Corak property

The geology of Corak is broadly similar to Tac, but with more intrusions by basic and acidic dykes and sills, and with more economic concentrations of gold, lead and zinc, rather than Tac’s gold and copper. More to the point, the gold grades are about five times richer at Corak than at Tac.

In the 1988-92 period at Corak, similar to its efforts at Tac, Cominco carried out grassroots work and drilled 85 RC holes (7,300 metres) and 9 diamond-drill holes (1,400 metres). Geologists delineated two significant mineralized zones, named Village and South.

Using conservative cutoff grades and low base metal prices that probably underestimated the base metal content, Cominco estimated that Village and South contained a combined 1.5 million tonnes of 10 grams gold. Again, this figure is not NI 43-101-compliant.

Mediterranean did little work at Corak in 2006, but came on strong in 2007 and completed 16,500 metres of drilling in order to produce enough data for the property’s first NI 43-101-compliant resource, expected this February.

“While we’re drilling, we’re learning a lot, and that is going to help us,” says Ibrahim Guney, general manager of Mediterranean’s Turkish subsidiary Akdeniz Resources Madencilik.

Before joining Mediterranean a year ago, Guney worked in Turkey for Cominco for eight years, then Inco for six months, and then Anatolia Minerals Development (ANO-T, ALIAF-O) for six years at its Copler gold project.

Recent drilling highlights from Corak include: 19 metres (from 89 metres) of 20.08 grams gold and 17 metres of 1.49 grams gold in hole CD-132 in the Village zone; and 65 metres (from 3 metres) of 1.37 grams gold in hole C-118 in the South zone.

Like Tac, Corak could be mined either as an open pit or from underground.

“Corak is turning out to be one hell of a project,” Guest says. “Now we’re thinking about whether we should put Corak into operation first, so it could fund the cost of a second plant at Tac. Some engi-neers have even told us that the potential is to have four or five operations along this trend.”

Last year, Mediterranean further broadened its horizons by starting to explore its 97 sq. km of permitted areas that effectively lock up almost the entire 12-km trend from Tac to Corak.

“This is a big system,” says Guney with a sweeping gesture across a geological map of Mediterranean’s claims. “This is not the end of the story, I think.”

In 2007, Mediterranean started a new scoping study for Tac, where an updated resource is expected before April, and stepped up the collection of baseline data at both Tac and Corak so there’s enough for an environmental impact assessment.

Wardrop’s office in London, England, is completing the scoping study while SRK’s Ankara office is tackling the EIS, which should be made easier by the fact that are no pre-existing environmental liabilities at Tac or Cornak.

Ore-quality material from both Tac and Corak was also sent to Process Research Associates in Vancouver for bench-scale metallurgical tests that generated recovery rates of around 90% for gold and copper.

“We want to define what kind of processing plant we’re looking at,” Guest says. “At first we were considering one single plant for both Tac and Cornak, but the economics and the sensible way to go is to put two plants in operation, one at Tac and one at Corak.”

There is enough room on the properties to store waste rock and tailings, though this has yet to be studied in detail, and water is readily available from the Coruh River.

Power play

For Corak to be mined, the entire village of Cemketen would need to moved, though, luckily, this time around for Mediterranean, there is little chance of this uncomfortable fact igniting another Tambogrande-style showdown.

Why? Because these small farms, villages and towns along the Coruh and its tributaries — including Yusufeli in the current proposal — are already slated to be inundated by a major new hydroelectric dam planned by the Turkish government 10 km downstream (northeast) of Yusufeli.

On the drawing board for many years, the dam has been pursued by the government slowly but relentlessly, casting a pall over the doomed villages and towns along the Coruh.

In this situation, Mediterranean could come across as the good guy, likely offering villagers at Cemketen, for instance, substantially more for their properties and handing out cheques much more quickly than would be the case for any dam-related compensation from the government.

As for the new dam’s effects on the Tac property, Mediterranean would likely see the road connecting Tac to Yusufeli and Corak flooded, and a new road would need to be built.

And of course, any open pits at Tac or Corak extending beneath the proposed water line would require careful engineering.

It’s still too early to say whether Mediterranean and the government can co-ordinate their respective efforts to their mutual benefit — for example, by using mine waste rock for dam construction.

“We’re proceeding as if this dam is going to happen,” Guest says. “So our whole design approach is to complement that.”

Turkey

In the broader scene, Turkey has an established mining industry and skilled personnel can be readily recruited from within the country.

But foreign miners have had a spotty record in Turkey in the past few years, with real successes tempered by such high-profile prob-lems as the closure by court order in August 2004 of Newmont Mining’s (NMC-T, NEM-N) Ovacik gold mine near Izmir (since sold to Turks) following a legal challenge by locals on environmental grounds, and Eldorado Gold’s (ELD-T, EGO-X) more recent headaches at its now-suspended Kisladag gold mine, also in western Turkey.

“Usually people have negative ideas about Turkey, but the road for gold mining development is open in Turkey, and it’s not going to be closed in any way,” says Sabri Karahan, a founder of Dama Muhendislik and a former manager at Ovacik.

“The challenge is the environmental impact statement,” he says. “Anybody in this country can take the matter to the courts without spending a penny from his pocket. This is unfortunately the case, and the cases can be repeated, unfortunately, over and over. The courts sometimes go wrong, that is true, but in the end, we believe they rectify it intelligently.”

That said, Mediterranean has a few important advantages in its Turkish operations: minimizing any potential anti-foreigner sentiment, all its in-country staff and on-site contractors are Turkish and there is no need for expats; the project is far from Turkey’s western cities and their environmental activists; there cannot be prolonged conflict over land use with locals, because they are already slated to be moved for the power dam; and any mine at Tac or Corak will primarily be milling and shipping concentrates, and not producing gold using controversial heap-leach cyanidation methods.

As money gets a little scarce in the junior mining sector, Mediterranean is in a good place financially: a

s of December, the company had $11.5 million in cash and no debt.

The stock traded at 25 in mid-January, near the bottom of its 52-week high-low range of 23-52. With 87.2 million shares outstanding, that makes for a market capitalization of just $22 million.

Major shareholders include RAB Capital, Teck Cominco, two Metage funds, Sentry Select, JP Morgan Asset Management, Macquarie Bank, Geologic Resource Fund and Fairlane Growth Fund, while one or more of the post-Peru financings were led by Northern Securities, Haywood Securities and London-based Loeb Aron & Co.

With the stock wallowing at a low level, many of the company’s outstanding warrants are underwater.

Meanwhile, Mediterranean continues to hunt for new mineral opportunities globally.

Comments Guney: “We are searching for possible other advanced projects in Turkey and in neighbouring countries like Georgia, Syria and Armenia, that we could operate.”

To sum up, it’s entirely reasonable to project that Mediterranean could soon have in its grasp at Tac and Corak two 1-million-oz. gold deposits with significant base metal credits that can be swiftly brought into production, particularly if the open-pit approach is chosen.

Not a bad comeback after hitting the wall in Peru just four years ago.

Be the first to comment on "Mediterranean develops gold-copper belt in Turkey"