The historic state visit of Vietnam’s number two man, Prime Minister Phan Van Khai, to Canadian and American soil in late June — the first visit to either country by a top-level Vietnamese government official in two generations — brings into focus two triumphs of interest to North America’s miners.

The first triumph is by Toronto-based junior Tiberon Minerals, which, along with its two Vietnamese government partners, is advancing its 77.5%-owned Nui Phao tungsten-fluorspar deposit, situated north of Saigon in northern Vietnam.

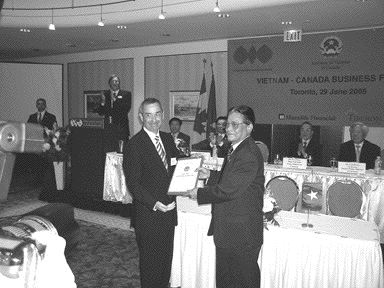

Since trailblazing into Vietnam in 1997, Tiberon has slowly but surely developed Nui Phao into a robust tungsten deposit. These efforts culminated in a watershed moment at the Toronto Board of Trade on June 29, when Phan Van Khai presented Tiberon President and CEO Mario Caron with a mining licence for Nui Phao — and this before Tiberon has even completed a full feasibility study!

To be built at a cost of US$211 million, the Nui Phao mine will have a throughput of 3.5 million tonnes of ore per year, and annually produce concentrate containing 4,300 tonnes of tungsten, 223,000 tonnes of fluorspar, 5,500 tonnes of copper, 3,000 ounces of gold and 900 tonnes of bismuth. Operating costs are estimated at just US$7.92 per tonne of ore.

In short, little Tiberon is well on its way to becoming one of the world’s largest and lowest-cost producers of tungsten and acid-grade fluorspar.

Tiberon has also smartly positioned Nui Phao as a significant non-Chinese supplier of tungsten in the future. The metal is considered strategic, owing to its use in armaments and specialty metals.

Light-bulb manufacturer Osram Sylvania has already signed on to buy 44% of Nui Phao’s output in the first five years of mining, commenting that Tiberon “offers a strong supply position that allows us to strategically diversify our material sourcing.”

The licence grant also confirms the wise choice of the Tiberon board in making Mario Caron president two years ago. His mining experience and smooth, diplomatic style have been crucial in guiding Tiberon from explorer to developer status.

(Caron’s success with Tiberon also means he can at last put behind him what must have been a frustrating experience in his last leadership role as president of Eden Roc Minerals, the junior gold explorer in Cote d’Ivoire that crashed and burned around the turn of the millennium, and eventually turned into a meat-packing company in Peggy Witte’s hands.)

From the Vietnamese government’s perspective, Nui Phao will be the largest mining project ever built in the country, and create 400 skilled jobs locally. The mine will further diversify the economy from its staples of agriculture, oil and gas extraction, industrial manufacturing and textiles. (How many know that Vietnam ranks as the world’s second-largest coffee exporter, ahead of Colombia and only behind Brazil?)

Which leads us to the second major triumph, this one by the Vietnamese government in its transformation of the economy from a bombed-out basket case three decades ago to one of the fastest-growing economies in the world, second only to red-hot China in Asia.

After the victory of the communist North over the U.S.-backed South in 1975, the unified Vietnamese government used an economic model based on Soviet-style central planning right up until 1986, when, in the face of declining Soviet subsidies, the Vietnamese government launched its “Doi Moi” policy and began opening up the economy.

In 2000, the Vietnamese government passed its landmark “Enterprise Law” for small- and medium-sized businesses, opened a stock market in Ho Chi Minh City, and began easing currency restrictions.

December 2001 saw Vietnam ratify a bilateral trade agreement with its former foe, the U.S., in a move that is still causing U.S. tariffs across a broad range of Vietnamese products to fall significantly.

In economic terms, the Vietnamese government has had several major achievements in recent years: high but sustainable, real gross-domestic-product growth rates above 7%; reduced inflation; manageable external debts and fiscal deficits; a stable currency exchange rate; trade liberalization; banking, tax and accounting reforms; and a significant reduction in poverty.

Perhaps the most surprising Vietnamese statistic is that, out of a purchasing-power-parity GDP that now stands at US$183 billion (or US$2,300 per person), the private-sector share accounts for 61%.

Some 34 million Vietnamese are now employed by the private sector (out of a total population of 82 million), and some 8,560 private enterprises were registered in Vietnam in 2004.

At the same time, between 1990 and 2005, the number of state-owned enterprises in the country dropped to 3,800 from 12,300.

Foreign direct investment (FDI) is no longer anathema to Vietnam’s socialist government; rather, FDI is a pillar of the new Vietnam. FDI has risen from US$100 million in 1990 to US$5.7 billion in 2003-04, with the biggest contributors coming from Europe (46%), East Asia (35%), South-East Asia (14%), and the U.S. (5%). By country, though, the biggest investors are still Asian: Taiwan, South Korea, Japan, and Singapore.

Geopolitically, Vietnam has reintegrated into the world: the country is now a member of ASEAN, APEC and ASEM, and is pushing hard to obtain World Trade Organization status.

Foreign donors like what they see and have pledged US$6.2 billion in development aid to Vietnam for the 2004-05 period. Another US$3.3 billion is funnelled into the Vietnamese economy each year in the form of remittances from overseas Vietnamese.

While manufacturing workers in the Americas — from union members in Ohio to seamstresses in the Dominican Republic — are getting hammered by competition from low-wage workers in China, Vietnam is actually positioning itself to undercut China’s wage earners dramatically: the average income for an unskilled worker in Vietnam is US$500 per year, or less than half of China’s US$1,100 figure. Professionals, such as engineers, are paid at a rate about 70% those of their Chinese counterparts.

The Vietnamese government isn’t even bothering to paper over its race-to-the-bottom industrial strategy: “The slow and smooth depreciation of the dong, without disruptive change to debt-service burden, is key to export competition,” says Vietnam’s minister of finance.

Most disturbing is that all of the commendable economic progress is being brought about with almost no loosening of the absolute political and social control wielded by the Communist Party of Vietnam over the average Vietnamese citizen.

We end up with a frighteningly stable political-economic entity, pioneered by China, that is at odds with the advancement of human liberty: a market economy watched over by a ruthless, tyrannical government. Or, as Tan Range Chairman Jim Sinclair would put it, we see in Vietnam another successful case of “authoritarian free enterprise.”

It’s a profound challenge to Western liberal democracies, and a trend that shows no signs of going away any time soon.

Be the first to comment on "Learning at China’s knee"