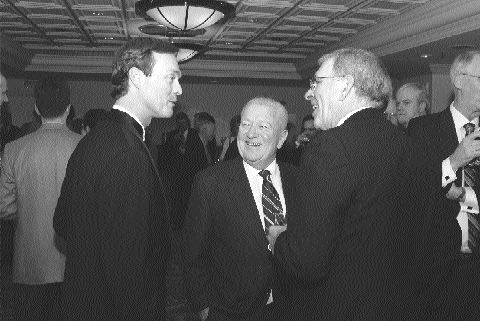

An audience of about 600 people attended a banquet to celebrate the achievements of four new inductees to the Canadian Mining Hall of Fame.

The 17th annual induction ceremony was held, as usual, at the Fairmont Royal York Hotel in Toronto.

This year’s inductees are all deceased. However, Alan Kulan, Adolphe “Lap” La Prairie, W. Austin McVeigh and Dr. J. Tuzo Wilson have each left behind vibrant legacies.

Master of Ceremonies Chris Hodgson, president of the Ontario Mining Association, summarized the achievements of each inductee, following which family members and others shared amusing anecdotes. The order of presentation was as follows:

Alan Kulan (1921-1977)

Alan Kulan discovered the Faro lead-zinc mine in the Yukon.

He took up prospecting after serving in the Canadian Army during the Second World War. In 1953, he discovered lead-zinc prospects by Vangorda Creek, near Ross River. Eleven years later, he formed Dynasty Explorations. That company merged with Cyprus Mines to form Anvil Mining, which found and developed Faro. The mine operated for more than 20 years.

Kulan continued prospecting and, in the 1970s, found the first occurrence of a phosphate mineral, which was named “kulanite” in his honour.

Kulan’s son Barry said his father had a lucky career, but went on to quote Thomas Jefferson, who said: “I am a great believer in luck. I find the harder I work, the more I have of it.”

Barry said his father had everything a prospector needed — “not only a thorough knowledge of minerals and geology, but patience, vision, courage, persistence and optimism.”

He summed up his father’s character with a quote from George Bernard Shaw: “Do not follow where the path may lead; go instead where there is no path and leave a trail.”

Adolphe La Prairie (1893-1976)

A pioneer in the explosives industry, Adolphe “Lap” La Prairie helped develop safe standards for working with dynamite. Later in his career, while working for CIL, he patented the underwater “air curtain” technique, which is still used by mining and civil engineers.

The first air curtain was used by Ontario Hydro. The procedure protected the hydro installation at Niagara Falls, allowing Ontario Hydro to blast within 30 metres of the power-generating station without necessitating a shutdown. (La Prairie used to quip that after saving Ontario Hydro more than $1 million, he still had to pay a hydro bill each month.)

Between 1920 and 1940, he worked as a manager for CIL in Timmins, Ont., helping miners solve blasting-related problems. He developed different formulations of dynamite to blast different rocks.

La Prairie’s blasting expertise was used on major construction projects, such as the St. Lawrence Seaway, Kitimat Power, and the Trans-Canada Highway.

He was transferred to Toronto in 1940, by which time he had nine children. Four of them were given names whose initials are abbreviations used in the explosives sector: Leon Frederik La Prairie (LF is short for low freezing dynamite); Carl Xavier La Prairie (CXL is short for Canadian Explosives Ltd.); Clifford Irwin La Prairie (CIL); and George Eugene La Prairie (GEL, or gelatin dynamite).

La Prairie was community-minded, and spearheaded a local charity event that was similar to the Santa Claus Fund in Toronto. At the induction ceremony, the mayor of Timmins, Victor Power, said Timmins owes a great deal to La Prairie and his family, whose interest in the community continues to this day.

La Prairie sold dynamite, by the stick and by the trainload, and helped train army personnel during the war. He had a knack for storytelling, which his son Leon inherited. Leon told the crowd: “My Dad went up to Timmins in 1920 as a salesman. We’ve never said why he was such a good salesman. I don’t want you to repeat it after tonight, but he was the only salesman, and CIL was the only company that sold powder in Canada. You had to buy it from him!”

Leon reminisced about the early days in Timmins, when everyone in town would come out to see the greasy pole contest: a 10-lb. ham was hung from the top of a greased pole, and sometimes the miners would even send their wives up to try to retrieve it. “It was Depresssion days at the time,” he added.

W. Austin McVeigh (1882-1975)

A love of the outdoors led W. Austin McVeigh to take up prospecting in the 1920s. He worked in Ontario’s Red Lake area, and later, in 1934, discovered the gold-bearing veins that formed the Madsen mine, which went on to produce 2.6 million oz. A few years later, he began working as a prospector for Sherritt Gordon Mines and discovered the Lynn Lake nickel-copper deposits in Manitoba.

Ian Delaney, chairman of Sherritt International, spoke about McVeigh’s legacy and pointed out that he found the Lynn Lake showings at the ripe age of 60. He added that that in itself should give encouragement to the many grey-haired members of the audience.

Garfield MacVeigh, chairman of Rubicon Minerals and a probable relative, spoke about how Austin’s tales of prospecting inspired him to follow suit. (Rubicon continues to explore a property in the Red Lake area — one that Austin had found for Sherritt Gordon and that Rubicon optioned in the 1990s.)

J. Tuzo Wilson (1908-1993)

Dr. J. Tuzo Wilson studied geology and geophysics and later got his private pilot’s licence. In the late 1930s, he was one of the first people to use air photographs to assist with geological mapping.

Wilson started out as a cook’s helper near Wawa, Ont. After a short stint in the kitchen, he was hired as a field assistant to a geologist who was mapping and exploring the Lake Superior region. Wilson was not one to limit his experience, so he worked for a while as a driller’s helper underground before returning to the bush and mapping some more.

During the Second World War, he worked alongside miners who were assigned tunnel-building operations for the war effort.

After the war, he worked for 28 years as a professor of geophysics at the University of Toronto. While there, he developed the theory of plate tectonics, which is the basis of geological knowledge today. From 1967 to 1974, Wilson was the first principal of the U of T’s Erindale College. He then spent 11 years as director of the Ontario Science Centre in Toronto. Wilson was awarded 15 honorary degrees from Canadian and U.S. universities.

Dr. Jerry Mitrovica, a geophysics professor at the U of T, said Wilson once gave him some valuable advice: “Be curious. Take risks. Be innovative. What have you got to lose?”

Wilson’s daughter Patty said her father once told her that if you develop an interest in rocks, the world is fascinating regardless of where you are.

“He was very fond of miners,” she concluded. “He knew many who are in the Mining Hall of Fame and would be proud to be in their ranks.”

The induction ceremony was sponsored by the Canadian Institute of Mining, Metallurgy and Petroleum, the Mining Association of Canada, the Prospectors & Developers Association of Canada, and The Northern Miner.

Members of the Hall of Fame are chosen for their contributions to mining in any of four general categories: exploration; building a corporation; technical contributions; and contributions to the role of mining in society.

The deadline for nominating the next slate of inductees is July 31.

Be the first to comment on "Kulan, La Prairie among inductees into Canadian Mining Hall of Fame"