“It’s not a huge resource,” says Pierre Vaillancourt, an analyst with Orion Securities. “You start small with this (mine) and you build your way up to something that will be more respectable.”

In terms of share value, Avnel could use some respect soon. With the exception of a 2-day run-up to $1.25 in late August, shares have been relatively stagnant at $1-$1.05 for the last two months. And with more funds needed for future exploration, a turn to the market could prove disappointing — as it was in June when Anvel’s initial public offering was only able to raise US$7.6 million instead of the US$12-US$15 million the company had hoped for.

The situation has Avnel’s Chief Executive Roy Meade looking at other options.

“Although we are small now, when we are at full production, cost will be in the US$200 per ounce range and that will help us fund our exploration,” Meade says.

Cash flow would be larger now were it not for Avnel’s hedge position — 60% of the company’s gold production has been hedged at an average of US$427 per oz. through to March 2007. Currently, the spot price for gold is about US$475.

Howard Miller, Avnel’s director and chairman, says in hindsight the hedge hasn’t been optimal for the company’s profitability, but it gave Avnel the security it needed at the time. Miller says Avnel couldn’t afford to take a chance on financing the completion of the Kalana mine, and on early exploration.

Meade says the company will “continually review its position related to any hedging beyond 2007.”

Gold production and exploration are taking place on the 387-sq.-km Kalana concession in the West African country of Mali.

Gold is currently being produced at the Kalana mine, where production will be ramped up to capacity at 25,000 oz. by 2007. As production rises, Avnel anticipates that costs will fall. For the remainder of 2005, gold production costs are forecast to be roughly US$425 per oz. but Avnel says that number will be cut to US$277 per oz. for 2006. Further cost reductions are expected to bring Avnel into Meade’s desired US$200 range by 2008.

Proven and probable reserves are 967,000 tonnes grading 14.1 grams per tonne for a total of 439,000 oz. gold.

The reserve comes out of a measured and indicated resource of 3 million tonnes at 10.4 grams per tonne for a total of 1.02 million oz. gold. Additional inferred resources average 3.4 grams per tonne for a total of 249,000 oz.

Production on the permit is run under the SOMIKA name, a subsidiary of Avnel in which the company has an 80% stake. The Malian government holds the other 20%.

Miller describes gold production at the mine as “economically robust,” and says Avnel is in no hurry to pull all the gold out of the ground. Instead it will “pause” and use cash flow from the mine to further explore promising deposits elsewhere on the property.

Recent diamond and reverse-circulation (RC) drilling has indicated two high-grade gold zones — The Djirila Main zone and the Djirila South zone.

Testing indicated 73.6 grams of gold per tonne over 2 metres from 70 to 72 metres and 45.9 grams of gold per tonne over 4 metres from 114 to 118 metres. Testing on Djirila South indicated 5.4 grams of gold per tonne over 36 metres from 64 to 100 metres.

Miller wouldn’t rule out a turn to the market to fund aggressive exploration.

When asked about future financing Miller said, “we’ll either wait for cash flow from the mine in 2007, or issue more shares.”

But if Avnel turns to the market again, does it have the recognition a junior needs to maximize the amount of cash raised?

“They need to get some history behind them and deliver on what they say,” Vaillancourt says. “So far, so good, but let’s see what happens. It’s early.”

Another factor hampering the share price is the small size of shares available to the public, or the company’s “float.”

Meade says the smaller-than-anticipated float is due to one of the promoters participating in the issuing — Elliot Associates, which holds slightly less than 50% of the shares.

Avnel management holds roughly 40% of fully diluted shares.

Miller emphasizes the positives of a small float, such as offering some stability in share price.

“We don’t believe there are sellers in that group (of large holders),” Miller says.

Vaillancourt and other analysts are bullish on Avnel’s position in Mali. Despite being one of the world’s poorest countries, Mali is mineral-rich, and has a political atmosphere and co-operative population that have won the admiration of investors and experts around the world.

“The government is very stable,” explained Martin Klein, a retired professor of history at the University of Toronto, and an expert on Mali. “In some ways it’s the most democratic country in Africa.”

Klein said that along with cotton, gold is the most important resource in the country, and Malians have a proven history of dealing with the resource in a pragmatic and dependable manner.

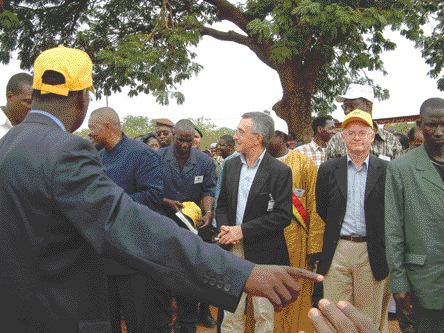

According to a Gold Fields Minerals Services survey, Mali is Africa’s fourth-largest producer of gold, behind South Africa, Ghana and Tanzania, respectively. But Mali’s president Amadou Toumani Toure has ambitious designs. At the opening of the Kalana mine in April, he said that Mali would leapfrog Tanzania and overtake Ghana as Africa’s second-largest producer.

“Mali is hot like Ghana was eight years ago,” Meade says.

The presence of larger companies like Randgold & Exploration (GOLD-Q) and

“It was a French colony, so it’s retained a French approach to business,” Meade says. “It’s bureaucratic, but very disciplined and relatively easy to do business there.”

It will be up to Avnel to parlay enthusiasm for Mali into enthusiasm for Avnel. To do so, it will have to assure investors it has something that other juniors in the region don’t.

One such assurance is Avnel’s 30-year permit for the Kalana property.

“Normally when starting up a project you get prospecting permits, then work programs,” Meade says. “Depending on that, they can extend the permit for a period. We’ve got (a permit) for 30 years and it gives us the right opportunity to do exploration at a realistic pace for a junior mining company.”

As CEO of Nelson Gold in the 1990s, Meade agreed to buy a majority stake of the property from Ashanti Goldfields. The Malian government thwarted the agreement, and subsequently stripped Ashanti of the permit and awarded it successively to two other juniors. But Meade believed the upside to Kalana was substantial, and he hung in.

“The government knew that we were there for every offering,” Meade said of the eventual awarding. “We were very persistent.”

Be the first to comment on "Avnel’s Malian operations small but stable"