There’s something about the allure of diamonds that tempts even the most conservative of mining companies. Since the unexpected discovery of the rich Ekati deposits in the Northwest Territories 20 years ago, majors from around the world have poured billions of dollars into Canadian diamond exploration and mining.

But the siren call can just as often lead to a money pit as it does to a profitable mine.

Australia’s BHP Billiton (BHP-N, BLT-L), then BHP Minerals, set the bar high in the early 1990s with the decision to back prospector Chuck Fipke in his pursuit of diamonds in the Northwest Territories. The gamble surprised analysts because an economic diamond deposit had never been found in Canada despite years of searching by diamond powerhouse De Beers. It was the late geologist Hugo Dummett, with his previous diamond experience, who managed to convince his employer BHP to take a chance on Fipke.

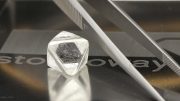

The end result of Fipke’s exploration work, the Ekati mine, produces 5% of the world’s rough diamond supply by value and earns hundreds of millions of dollars in revenue annually. BHP Billiton owns an 80% interest in the cash machine, which opened in 1998 and produces about 3 million carats per year. Fipke and his former partner Stu Blusson own the remaining 20%.

The nearby Diavik mine, owned 60% by Diavik Diamond Mines — a division of Rio Tinto (RTP-N, RTP-L) — and 40% by Harry Winston Diamond (HW-T, HWD-N) is another enviable success story. Production surpassed 50 million carats in 2008, five years after the mine opened. Diavik is currently making the transition from an open pit to an underground operation under improving market conditions for rough diamonds.

So it’s little wonder miners of all stripes have lined up to get a piece of the lucrative Canadian diamond sector. Over the past few years, Teck Resources (TCK.B-T, TCK-N), Newmont Mining (NMC-T, NEM-N) and Kinross Gold (K-T, KGC-N) have invested hundreds of millions of dollars collectively. But the alluring stones have proven to be fickle friends.

“When Ekati and Diavik were discovered, it was perceived that Canada could be the source of 50% of the world’s diamonds in the future because of its geology and the huge Archean craton where there are kimberlite pipes in the thousands,” says Pierre LeBlanc, principal of Canadian Diamond Consultants and former vice-president of corporate affairs for Diavik. “But with the exception of the big discoveries (including De Beers’ Victor mine), most of the pipes that have been found have not been sufficiently diamondiferous to be economic.”

Teck pays a hefty tuition fee

You don’t have to tell that to Teck. Four years ago, Teck (then Teck Cominco) spent $30 million to buy a 16% stake in Tahera Diamond, a junior company that had ambitions to become the leading Canadian-owned diamond company through its 100% interest in the Jericho mine in Nunavut.

“Our investment in Tahera is consistent with our goal of further diversifying our portfolio especially into non-exchange traded commodities,” Teck president and CEO Don Lindsay said at the time. “As we continue to actively explore for diamonds, we view this alliance with Tahera and its existing partners as an attractive opportunity to expand our knowledge of all phases of the diamond business from mining through marketing, while helping to add value to the Jericho project.”

Jericho turned out to be expensive tuition for Teck. The tiny mine, already having trouble meeting its production targets, ran into a perfect storm of insurmountable problems, including a premature closure of the winter road used to ferry supplies, lower than modelled grade, technical difficulties with the crusher that reduced output and currency fluctuations that finally killed the project.

Teck quickly backpedalled, choosing not to participate in a rights offering in December 2007 that was intended to rescue the mine and, later, writing down $22 million of its investment in Tahera. Tahera went bankrupt and Jericho was placed on care and maintenance in 2008.

“Teck had ambitions to move into the diamond sector on a broader scale,” says John Kaiser, who produces the Kaiser Bottom-Fish Online newsletter and has been closely following the Canadian diamond sector for several years. “But getting involved in Jericho didn’t make a lot of sense because it was never going to have a long life or generate a lot of cash flow.”

Since the Tahera experience, Teck has lost its lust for diamonds and moved onto much larger-scale investments in coal and oilsands. Jericho, meanwhile, may get a second chance to produce from Edmonton-based Shear Minerals (SRM-V), which has agreed to pay $2 million cash and 80 million shares for the mine.

Newmont lured by giant kimberlite field in Saskatchewan

Similar ambitions to Teck’s — combined with then-president Pierre Lassonde’s self-professed love of the diamond business — drove gold giant Newmont Mining to invest $50 million for a 10% equity stake in Saskatchewan explorer Shore Gold (SGF-T) in 2005, and another $170 million for a 40% stake in the junior’s Fort à la Corne (FALC) diamond property a year later.

Newmont had made a killing selling its equity stake in Aber Resources (now Harry Winston Diamond), part owner of the Diavik mine, and was hoping to repeat that success not only as a passive investor, but as a hands-on strategic partner. The thinking was that Newmont could contribute its technical expertise for operating open-pit, disseminated deposits to develop the kimberlites of the FALC project into a profitable moneymaker.

“In those days, Shore Gold was claiming, rightly so, that they were sitting on the largest kimberlite field in the world, with literally billions of tonnes of kimberlite material,” LeBlanc says. “So there was a high expectation that this was going to be a huge, very profitable operation and that Newmont could bring its mining expertise to the table.”

But four years later, the project is still in the advanced exploration stage and Shore Gold’s stock has dropped from a high of $8.75 per share in March 2007 to less than $1 today. Newmont’s $50-million equity stake is worth less than $7 million.

Newmont stopped putting money into the joint project at the start of the downturn in 2008, after the partners spent $87 million on exploration, including shaft-sinking on the Orion South kimberlite. The company has had little to say about the partnership since: it directs all inquiries about the project to Shore Gold and declined to comment for this story.

Meanwhile, Shore has forged ahead on its own, spending $8 million on its 100%-owned Star property nearby in 2008 and another $18 million on both projects in 2009, culminating in a positive prefeasibility study for combined open-pit mining of the Star and Orion South kimberlites.

The study is based on reserves of 279 million tonnes with an average grade of 12.5 carats per hundred tonnes, equal to 35 million carats and an average price of $226 per carat. Assuming a mine life of 20 years, the net present value of the project is estimated at $1.3 billion (using a 7% discount rate), while the internal rate of return would be 16% before taxes and royalties. Total capital costs are estimated at $2.5 billion.

By comparison, the Diavik feasibility study completed a decade ago was based on minable reserves of 25.6 million tonnes averaging 4 carats per tonne, equal to 101.5 million carats and an average price of $63 per carat. Predicted life-of-mine capital costs were $2 billion.

Be the first to comment on "A major gamble"