🎥 Watch the video: [English] | [French]

🗞 Read the full article in French

In the far northwest of British Columbia lies a place few Canadians can name, but where billions of dollars’ worth of gold, silver and copper still lie buried beneath glacier-topped mountains and untamed forest. This is the Golden Triangle. Once the wild frontier of stampedes, now the epicentre of a modern mineral revival.

But before the helicopters, drills, and billion-dollar valuations, there was a single man – an irrepressible, wayward Quebecois named Alexander “Buck” Choquette – who stumbled into its riches and reshaped its destiny.

A boy against the grain

Long before he was “Buck,” Alexander Choquette was just another boy born into tradition. In the seigneurial village life of early 19th-century Quebec, his path was set from birth: Jesuit schooling, life close to the church, and a marriage chosen by his elders. Certainty was the currency of his family. But Alexandre had no use for certainty.

At ten, he was skipping mass to fish. By fifteen, he’d had enough. One morning, he packed a heavy lunch, walked out of his family’s world, and never looked back.

His first stops were small towns. He chopped firewood, delivered packages, and worked odd jobs for board. He slept under trees, in barns, or with farm families who asked few questions. In Montreal, he worked for an apothecary but hated being indoors. Restless, he headed west again.

In Winnipeg, then still known as Fort Garry, he flirted with the fur trade. But he wasn’t after beaver pelts. He wanted freedom. News travelled slow, but it travelled: gold had been discovered in California.

Into the Wild West

By 1849, California was boiling with gold fever. Choquette joined a wagon train of tough men heading west from Missouri, wearing buckskin, which earned him a new name from fellow travellers: Buck.

California was both paradise and hell. Gold dust poured from creek-beds –and so did greed. Buck made enough to get by, but never finished first. Always a day late to the richest strikes, always moving. When not panning, he fought off claim jumpers, racism, and the cold hostility of Anglo Saxons who saw him as another foreigner.

Still, he endured. When the crowds moved on, Buck moved north.

He followed the veins of gold through northern California and southern Oregon – Shasta, Yreka, the Trinity River, Josephine Creek – living like a hawk, surviving off the land, chasing stories. By 1857 he’d made his way into British territory and joined the early rush on the Fraser River.

But again, the best claims were gone.

What he heard next would change everything: there was a vast, untapped river far to the north. No real roads. No maps. Just stories and possibilities. The Stikine.

Golden era

In 1859, Buck reached Victoria, looking to pass up the coast. He found it not with colonists, but with the Tahltan Nation, a group of Tlingit people heading home by canoe. They offered him a place among them. He took it without hesitation.

The journey up the Inside Passage stretched 1,300 kilometers. Narrow fjords, frigid rain, tides, sea lions, and killer whales. For weeks, they paddled north, deep into Tlingit territory. Buck earned their trust. He hunted with them, ate what they ate, and learned their language.

When they landed at the delta of the Stikine, everything changed again.

Buck met Chief Shakes, the respected leader of the powerful Stikine Tlingit. And he met Georgiana, Shakes’ daughter. She was smart, youthful and unafraid of the strange French-Canadian who had arrived with her people. They married that same year.

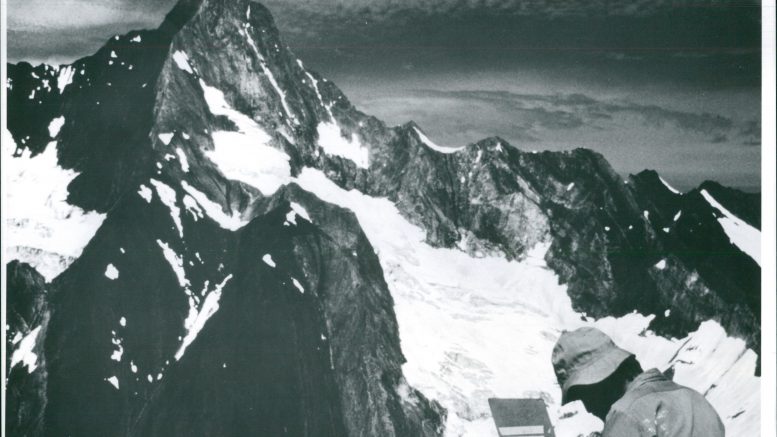

With Georgiana at his side, Buck pressed deeper into the wilderness. They travelled upriver through country no white man had dared cross. At one point, Buck stood before a glacier, awestruck. It calved thunderously into the water before him, pure white and ghost-blue. He called it Ice Mountain. The name stuck.

The Triangle takes shape

In the Fall of 1861, by Telegraph Creek, Buck stopped to pan in a spot that looked no different than the dozens he had passed. What glinted in his pan wasn’t pyrite. This time it was gold. Real. Heavy. Plentiful.

Soon others gathered and word spread. By Spring, hundreds were on their way. The first rush to the Stikine had begun.

The area came to be known as Buck’s Bar, marking the first real gold strike in what would eventually become known as the Golden Triangle. It sparked the Stikine Stampede of 1862, then the Cassiar Gold Rush a decade later. Prospectors poured in. Fortunes were made and lost.

Buck stayed, guided newcomers, raised a family with Georgiana and cemented his place in the lore of the North.

Though few recognized it at the time, Buck’s strike near the Stikine had cracked open the door to one of the world’s most mineral-rich regions. Over time, geologists would identify a triangle-shaped region stretching between the towns of Stewart, Telegraph Creek, and the Alaskan Panhandle. It became known as the Golden Triangle.

For decades after Buck’s discovery, other prospectors trickled into the region. Each wave seeking what he had found.

In 1918, Premier Gold Mine started operations and dazzled early investors. The mine’s backers saw 200% returns. For a time, it was considered one of the world’s richest gold-silver mines.

Later, the Snip Mine, first discovered in 1964, would yield nearly a million ounces of gold. Then came Eskay Creek, where drill holes pierced through to a motherlode so rich it redefined Canadian mining: 49 grams of gold per tonne, 2,406 grams of silver. Production soared. Share prices exploded. But as quickly as fortunes rose, the mines closed.

By the late 1990s, gold prices had collapsed. Gold hovered under $300 per ounce. Labour and logistics in the remote Triangle were too costly. Despite the quality of the deposits, the region’s mines shut down and exploration faded.

But the gold was still there. Waiting. Modern technology was about to wake it up.

Awakening the giant

Today, the Golden Triangle is roaring back to life.

Three things changed everything: higher gold prices, new infrastructure, and smarter exploration. Road networks once impossible are now punched deep into the terrain. Drones and 3D mapping have replaced guesswork. Helicopters and power grids reach where they never could before.

Massive new finds have reignited the rush, with over 150 mines operating here since the late 19th century.

By 2020, the Triangle accounted for nearly half of all exploration spending in B.C. By 2024, it had grown to over 63%. Today, it also it accounts for around three-quarters of Canada’s known copper reserves.

Yet, as of 2017, only 0.0006% of the Triangle had actually been mined.

At the Valley of the Kings deposit, Pretium Resources tapped into another high-grade vein. At Seabridge’s KSM project, billions of dollars in copper and gold await development.

At Newmont and Imperial Metals’ Red Chris gold-copper mine production is already adding hundreds of millions to B.C.’s economy.

Another leader of the region’s revival, and spending C$713 million to re-open by 2027 one of the world’s former highest-grade gold mines, is Skeena Gold & Silver. Recent government investment in the region is “a pivotal moment for our critical minerals industry,” CEO Randy Reichert has said.

The Vancouver-based Skeena is pushing hard for production at Eskay Creek as it’s now fully focused on construction.

The provincial government announced in June this year its commitment to “seize the potential in the northwest.” Premier David Eby said his government aims to align industry, First Nations and conservation interests.

B.C.’s Critical Minerals Minister, Jagrup Brar, noted the plan aims to align provincial and federal reviews. He mentioned the goal is “one project, one review.” Brar also said the government wants to pursue trade agreements that focus on B.C.’s minerals and metals.

Silver shine

Focused on the region’s silver potential, Dolly Varden Silver is exploring its Kitsault Valley’s Wolf deposit. The high-grade primary silver deposit is unusual in the silver mining world, according to the company, since the metal is typically produced as a by-product.

The company also encountered exceptional gold grades at its Homestake deposit.

For Goliath Resources, almost every hole of the 100,000 metres drilled at the Surebet discovery has returned gold, CEO Roger Rosmus said in a recent interview. The company started drilling another 38,000 metres in May.

What would Buck think of it all? Modern explorers catching a helicopter in Terrace and buzzing the mountain ridges, the drill cores, the billion-dollar valuations? Likely, he’d shake his head, shoulder his pack and head upstream.

He didn’t chase gold for the money. He chased it for freedom. The possibility. The thrill of being the first.

But thanks to him, others followed. And they still do.

The Tahltan, his adopted people, now play a central role in development, ensuring that the land is respected and that the benefits flow to the communities who live there.

The wilderness remains brutal and beautiful. Ice Mountain still looms, unchanged since the day Buck first stood speechless before it. The rivers still cut through canyons where eagles fly and salmon run.

But beneath it all lies the gleam that first called Buck Choquette north. It’s still there, waiting.

And the next great discovery might be just one pan away.

Note: This article is part of The Great Canadian Treasure Hunt. Typos aren’t clues… or are they?

Be the first to comment on "The Northern Miner Treasure Hunt – Golden Triangle Dreams: From Buck to Billions"