Half a day south of the N40 highway in Pakistan, the main road heading west to Iran through the Balochistan desert, lies the Ras Koh mountain range. Steep, rugged mountains with little or no forest cover cut by deeply incised nallas, or dry stream beds, which you don’t want to be stuck in when it rains.

Not that it rains very often. I was there in 1997 prospecting for porphyry copper systems, hot on the heels of BHP’s massive Reko Diq discovery in the Chagai Hills.

Baking roti in the field in Pakistan. Photo by Ralph Rushton

Getting there was a two-day drive from Quetta along the N40, dodging Iranian and Pakistani trucks. The driving was some of the worst I’ve ever experienced — if you ask me, it’s a bloody miracle any trade ever makes it across the Iran-Pakistan border in one piece.

Local Pakistani policeman, who had just invited us in for tea. Photo by Ralph Rushton.

Heading south, you might come across convoys of armed pickup trucks smuggling opiates to the Makran coast.

And then there were the delightfully named “camel spiders” — hairy orange buggers with huge jaws that may or may not eat camels.

With only a very basic map and a GPS, accompanied by a dignified elderly Pakistani geologist, Naseem (who spoke Baluchi) and two government soldiers, I was trying to find a way in to the centre of the Ras Koh range.

Detailed satellite image processing in the head office had flagged a large area that looked like it might be a porphyry-related alteration system that had to be checked.

But after two days of hiking we gave up. There was no easy way in that didn’t involve some pretty extreme camping, and we simply weren’t equipped for it.

Naseem recommended visiting the local governor to find out if there were any tracks or roads that we hadn’t tried, and off we went to find him in Dalbandin.

Pakistani border post seen from just inside Afghanistan. Photo by Ralph Rushton.

Dalbandin

Dalbandin was a particularly unpleasant little truck-service town. Dirty and hot, with — back then — only the cockroach-infested government hostel to stay in.

What followed was a traditional tea-and-cake session with the governor to honour the foreigner (me) — any excuse for a nice slice of jam sponge.

After a couple of hours reminiscing about the glorious legacy of the British Empire (I kid you not), he looked at our map and drew a large triangle around the area we’d been trying get into and said in perfect English, “Stay out of here” — with no explanation given.

On the way out, Naseem told me in a polite but insistent manner that we should forget about that particular target and move on.

We headed west to Fort Saindak to chase different targets — a possible volcanogenic massive sulphide system — out on the westernmost point of Pakistan where the Iranian, Afghan and Pakistani borders meet.

The British colonial-era Fort Saindak, far west of Balochistan. Photo by Ralph Rushton.

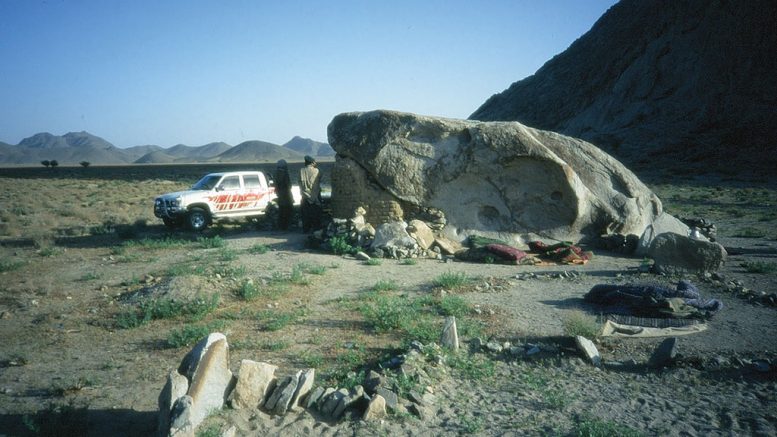

Pit stop in the Ras Koh ranges. Photo by Ralph Rushton.

Six months later, the Pakistanis detonated five atomic bombs at their top-secret test facility in the middle of the Ras Koh range.

Our satellite photos had picked out the spoil heaps from the underground tunnel excavations. I’d been trying to hike into a remote nuclear test facility — a Westerner with a digital camera and a GPS.

Thankfully, I’d listened to Naseem’s advice.

— Ralph Rushton is an exploration geologist who prospected the Tethyan belt from Bulgaria through Turkey and Iran, and into western Pakistan, in the mid-1990s.

I‘m just grateful I didn‘t know any of this or any other adventures you had.